Breadth | vector poem

As of 2009, the game industry seems to want two fairly contradictory [1] things:

- Make games, using proven mechanics from the last 20 years, that sell millions of copies.

- Give people a broad range of experiences that affect them as powerfully as those found in other forms of art.

Visual aids are nice so here’s one for each of those:

Hot New Video Game Consists Solely Of Shooting People Point-Blank In The Face

(Ignore the kid yammering over the video, until about 1:10 in, for the quicktime event sequence.) [2]

We can debate whether encompassing a broader range of human experience is indeed a goal of importance, but if even a God of War game feels the need to have a scene like the one shown above, you might at least concede that it’s something many developers seem interested in furthering.

To cut right to the heart of the conflict I see here, I don’t think we as developers can continue holding our breath and waiting for games that revolve around shooting, driving, running and jumping to someday make a great leap into expressing all kinds of things they were heretofore incapable of.

The problem is that the better versed you are in game conventions, the easier it is to separate the core mechanics of a game from its fiction and theme, and thus say that a game like BioShock is a meditation on free will, the dangers of ideological extremes, and whatever else… despite the fact that you spend about 90% of it shooting people in the face.

On top of simply being good satire, the Onion piece cuts to the heart of that, and reminds us that rest of the world can see this disparity more clearly, ironically by virtue of being less game-literate. For many among the gaming literate, that sort of insight hits pretty close to home.

For a perspective from the other end, I was struck by this comment on io9, a non-gamer blog, from this post about BioShock 2:

I can see how a first-person shooter would be interesting and entertaining, but I would have to fall short of “compelling” when you have to spend that much time, er, shooting.

This person wasn’t being an unreasonable jerk, or advocating the censorship of games. Shooting lots of insane people in a dark, weird place probably just isn’t their idea of a good time.

The common response to this from developers has been things like, “We just need to hire better writers”, “We need better technology”, “We need better artists”, “We need to spend more time planning out our stories”. However, we’ve been doing this for more than 10 years. Whereas if you look at the points where this medium has made the most progress, whenever the expressive capabilities of games have expanded significantly, it’s actually been because new mechanics, or significant developments upon existing ones [3], have emerged that enable new aesthetics. Those other things are quite important, but we seem to have them covered.

One problem is that, deep down, many designers view game mechanics more as structure (or “form”, if you prefer) than as content, when in fact they are both. If you treat them exclusively as structure when designing, you get all manner of unintended message and context… in a nutshell, ludonarrative dissonance. Which in 2009 means mashing the circle button to overcome an emotional inner conflict. Another designer’s analysis accepts this completely at face value, which if anything demonstrates that this issue transcends our usual valuations of craft and art. It’s almost invisible to us, but quite apparent to outsiders.

So as developers, we need to deal more honestly with the disparity between our reach and our grasp – which is to say, what we tell ourselves our games are about, versus what they are actually about. History will see this decade as the period when games struggled with their destiny in this way.

I’m optimistic though, both because of the progress we’ve made in the first three decades or so of our medium, and because the solutions are right under our noses, deep in the fabric of all games. We must search out, and in some cases rediscover, core mechanics that engender new types of experiences – rediscover, because many have already been done at the fringes, promising yet underexplored. Here are some examples I find especially interesting:

AI Companionship: Holding hands in Ico

You reach out to a non-player character and become connected to them. Suddenly you’re no longer a lone entity; you must account and take responsibility for an Other. Sometimes they’re a hindrance, sometimes a help. Whether or not you buy into the designers’ attempts to make you sympathize, you have a real connection to something that’s reinforced by strong kinesthetics. In Ico, there was plenty of platformy adventuring to go along with this, but it seems inevitable that someday a game will make this its primary emphasis.

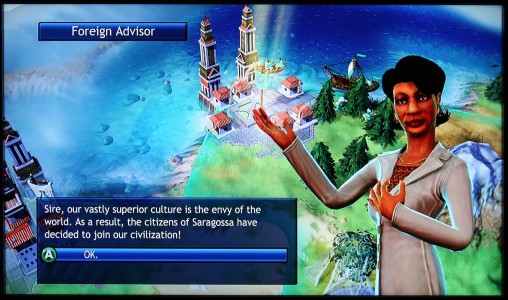

Victory via Self-Enrichment: Culture in Civilization

Sometimes you can triumph over an adversary simply by being better than them. Rivals come to view your achievements as an example to be followed. Each accomplishment that enriches you internally affords you expansion and encroachment via indirect force. Tend to your own garden and you will become powerful and influential without firing a shot.

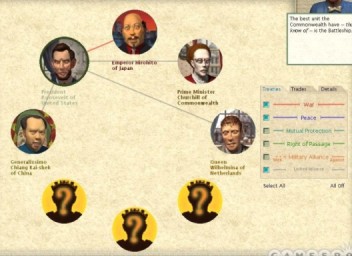

Social Reasoning: Diplomacy

The enemy of my enemy is my friend. Many wargames have a diplomacy component, which gets especially interesting when other humans are in the mix. However in a game where direct force isn’t possible, social standing would be its own capital. This is a large part of why character-driven TV shows are popular; humans enjoy exploring the workings and permutation spaces of social networks.

Hopefully this gives an idea of the breadth of directions available to us as designers. It’s equally fruitful to look to the past, at how certain ideas bubbled up from nowhere to expand the expressive range of games.

Circa 1997, before Thief and Metal Gear Solid, Stealth was one of those underexplored mechanics. Suddenly, as it caught on, there were new play sensations we’d never had before – being some combination of sneaky, clever, afraid, transgressive. It transformed players’ perspectives on familiar game environments. It even brought some new people into the medium.

These are basic changes that everyone feels deeply, from a jaded critic to someone completely new to games. They are interactively “true” in ways that a change in setting can only rarely be, no matter how beautifully realized.

As a medium, we’ve proven we can seek out novel settings, themes, art styles, characters and tropes. We have other media to learn from, after all. New mechanics, however, are uniquely difficult. The only inspiration we can find for them is human experience itself, and then comes the struggle of synthesizing, systematizing and iterating. This is the central challenge of working in this medium, and it’s never been more important that we embrace it.

[1] While some of this could be explained as the disparity between what game publishers want and what developers want, that might be giving too little credit to the former and too much to the latter. If there were more proven game mechanics and styles that enabled new experiences, publishers would probably sell them. Past a certain point, the burden of proof is on us.

[2] I want to make it clear that I’m not disparaging GoW:CoO, or speaking in any sense other than constructive criticism. I haven’t played it; in all likelihood it’s a great action game. I’m simply holding it up as an unwitting example of a much more existential crisis in game design today, much as other designers have held up stuff I’ve worked on in a similar light.

[3] Movement is something that gets re-discovered every so often; Mirror’s Edge being the recent example. Flaws in execution aside, players recognized there was something unique there.

April 18th, 2009 at 11:07 am

Warning: excessive caffiene. You know what I’m like on caffiene.

“I don’t think we as developers can continue holding our breath and waiting for games that revolve around shooting, driving, running and jumping to someday make a great leap into expressing all kinds of things they were heretofore incapable of.”

Granted. At the same time, there’s a lot of expression space available to the player which most games don’t (but potentially could) acknowledge. Some of these expressions are only percievable/accessible to the well versed (appreciation of good blocking and combos in StreetFighter 4). Other expressions could be siezed on by the game, and represented in a form more appreciable to the lay person (when a “6 hit combo” notifier pops up) who might otherwise not notice the significance of what just happened.

The closer the representation of these subtleties gets to the affordance/typical reaction to the verb itself, the more naturally interpretable the “finesse” of the expression is to the lay person (i.e. crowds cheering in the background when a technically impressive feat goes off).

Unfortunately, chucking “+10 XP” on the screen is way cheaper than providing the full gamut of possible reactions to a scene. We tend to have to use short-hand to get “finess” across, and it’s something the lay person just can’t quite be bothered to learn to translate.

There are loads of little promising ways we already do this, as you say. Some examples from me: Threatening enemies by pointing a gun in their face as opposed to simply shooting (in GTA:3 you can make people raise their hands or flee in fear); in Assassin’s Creed, doing a multi-kill combo in open combat with the hidden blade actually causes guards to run away due to your show of prowess, rather than chucking up an abstract (and possibly “gaudy”) “MMMMM MEGA KILL x 8” popup.

Any verb with a varied expression space can be used to trigger more subtle outcomes than its prime affordance: “your target is dead!”, “you jumped that gap!”, “you drove faster than another fastcar!”. Well versed gamers, of course, will appreciate the finesse in a gun shot the same way a ballet afficianado understands the meaning being articulated through interpretive dance.

In order to allow a wider appreciation of these subtleties, typically, we’re seeing “finesse” translated into the old fallback of “score” (i.e. The Club with its myriad of shooting style bonuses, or Skate and its ilk codifying style into score*). This is mostly because it’s the most practical solution on a limited budget (or plain love of retro tropes). We could, instead, create the natural responses we’d expect in the real world (but it’s more expensive, and harderer. And simulation is not necessarily a games’ target).

More could be done in this vein, adding weight and meaning to the tropey verbs we’ve become accustomed to. A gun no longer becomes just a killing too, but also a bargaining chip (we can buy, sell, and trade it for other goods or services), a symbol of power (in the kindom of the unarmed, the one gunned man is king), a threatening device (point, but don’t click), a last resort in a conversation (I live in brixton), or a piece of evidence after a killing (don’t get caught with a murder weapon – it’s a hot potato). We use something we know to be a good gaming “launch pad” to approach something closer to a more dramatic narrative element, in the storytelling sense.

But as I say, the amount of cost and effort involved in setting up decent core game play for a shooty, racey, jumpey game, and its frighteningly expensive (and often rigidifying) shiney vaneer means there’s little room to experiment with these subtle, but immersive ideas. Games which try to before the groundwork is laid often come off half cocked (not having time to fully flesh out their mechanics) or unpolished (though I thouroughly appreciate every game which tries).

Normally, I’d say “Yay for homebrew, the indie scene, and modding for being cheap enough to pick up the torch, and experiment!”, but for the most part, they’re up against the exact same problem. Their strength lies in experimenting with very base core mechanics, rather than supporting ones (no bad thing). They too need a core mechanic before they can start adding these supporting mechanics, which only really serve the game properly when put ontop of a solid frame work (Braid is successful here: without time-fucking it would be a vanilla platform game. Time fuckery is given its full due, and it’s an excellent game because of it. Contrarywise, FarCry 2 had lots of wonderful high level ideas, but no time to explore their full implications.

Civilization etc. stand a better chance of trying out social mechanics because they aren’t about technologically involved/costly core mechanics, and are free to play around with the design at that high level.)

Really, it goes back to creativity being a product of restriction. Within a limited production cycle, what mechanics are you going to choose, what story are you going to weave, and what are you going to say with them all together? There is a world of interesting, accessible things TO be said by more complex games (with solid cores, but enough supplemental depth/high level mechanics to create the necessary interactive richness for certain messages), but those more complex games rarely have the chance to exist, almost purely due to their impracticality.

*Which, yar, is a subjective application of seemingly objective values – a lot like review scores.

April 27th, 2009 at 12:09 pm

“Circa 1997, before Thief and Metal Gear Solid, Stealth was one of those underexplored mechanics. Suddenly, as it caught on, there were new play sensations we’d never had before – being some combination of sneaky, clever, afraid, transgressive.”

Speaking of transgressive, around then I noticed a new gameplay verb/emotion that a few games have since included, but few have really leveraged consciously as a main basis — voyeurism. Stealth can include this, but only when the designers go the extra mile to give you interesting/private things to listen/look at. Thief’s famous “Goin’ to the Bear Pits” dialogue was an early, if somewhat basic example of this.

Jordan Mechner’s The Last Express had a *lot* of voyeurism, even though it had fairly little stealth, per se. You could overhear conversations in the diner cars, you could go into people’s private cars when they weren’t there, and read their intimate diaries. Similarly, the logs and ghost scenes in the Shock games can give you a sense of seeing things that were intended to be private, even though they have no stealth at all.

The feeling of successfully prying into someone else’s private affairs is quite potent. Like “shooting in the face”, it’s a socially frowned-upon activity which most of us don’t get to indulge in in our real lives — but which is inherently pleasurable at a deep level. Games are a great way to satisfy those transgressive urges.

April 27th, 2009 at 10:38 pm

Aubrey, I’ve been mulling your comment for a while, and I think a lot of what you’re saying is about Depth. When we develop one of the known core mechanics enough, we get new expressions arising from that new depth. I was maybe hinting at this with my “re-discovering” statement, but as I settled on a title for this post I became primarily concerned with the new stuff at the fringes.

But of course there are frontiers deep down in the established mechanics as well, that are just as important to explore. After all, 2D shmups became artful only years after the mainstream industry had abandoned them.

I think what will get us there is a commitment to excellence in game design in the established styles – low level things that get surprisingly short shrift in most games.

June 30th, 2009 at 10:16 am

I am late to this discussion but would like to throw in if I may. The bulk of my comment will be about more understanding, seeing the big picture, and then responding as someone who loves games but is not (yet?) in the industry.

JP, the topic header confused me until I saw your response to Aubrey as “Depth.” My first question would then be what are the three (or more) aspects of Game Design? If one is Depth – the different ways I can use a tool, such as a gun; and one is Breadth – many ways to accomplish the same (or different goals) by companionship, enrichment, and reasoning – then what is the third? Secondly, I’d like to mention “System Shock Two” as an example of a game with potential Breadth and definite Depth. SS2 immediately sprung to my mind when Aubrey mentioned the many uses of a gun because SS2 did not have many uses for one tool, but did have many different tools. These tools were not available to everyone every play – if you choose to be great in guns, you were only okay in other areas and vice versa – and so created at least one session of replayability if not more. The variety of how you could deal with problems created that replayability: should I be invisible and sneak through? What about not taking any computer skills? There could be a dozen different personal scenarios to run yourself through and see how difficult you could make it.

A co-worker at a bookstore of mine did the same with BioShock but there is where I’d like to say the comparison ends. System Shock 2 was a playground with a definite entrance and a definite exit. There were definitely places I had to go but how I got there and what order I did them in was fairly loose. In many cases, I had to go back to former levels to acquire items I had no access to. This made an environment I was always paying attention to rather than forgetting once I had made it the next step further. A city to explore rather than burning a bridge behind me.

BioShock was, is, beautiful. The story and writing, but for a few places, were gorgeous and brilliant. The artwork, set design, level design, costume, modeling, was incredible. I could go on for a while about how visually appealing it looked but that would be exhaustive. It did. BioShock also had a variety of weapons and powers to choose from and the earlier mentioned co-worker played the game three times with different challenges for him to beat the game. The key differences in my mind, what cost it “Depth” if I’m using my metaphors properly, is that the world was railroad and everyone – for the most part – got everything. By the time I was finished playing BioShock the first time, with a healthy dose of information (read: unfair advantage) from other people I was actually at a loss of what to do with my Adam and cash by the end. I had everything, every power, every upgrade, maximum ammunition, everything. It was an incredible experience getting there and I have played it through again, but I still had everything. BioShock did not force me to make power related choices. Moral choices, yes. Capital Yes. But not strictly game mechanic choices. If I kill all non-entities, I will receive mostly maximum power now. If I do not kill these non-entities, I will receive slightly more power later. If I choose somewhere in the middle, I will fall somewhere in the middle. System Shock 2 completely cut you off from an entire range of abilities. You were either zero to useless in psionics, or zero to useless in big guns, or zero to useless in hacking. Very distinct, very different, none required to win the game, but all very useful in their own way.

If the above is a correct assessment of “Depth” or “different paths up the same mountain”, I’m afraid I don’t entirely understand “Breadth” unless you mean it is different paths leading to completely different mountains. Hopefully it doesn’t kill or alter a thing to define it, but how do I make a game with “Depth” and “Breadth.” And what is the third measurement if there is one?

May 1st, 2011 at 2:01 pm

[…] more different kinds of games. I believe more strongly than ever that broadening the range of human experience we simulate in our games beyond shooting, stabbing and jumping, is the most direct route to establishing games as a cultural […]

March 4th, 2012 at 8:13 pm

[…] while back I started to build a case for why I think the hyper-focus on combat mechanics in mainstream games is the primary thing […]